Complexity’s Revenge

Electric Power and AI

We need gas. We need nuclear. We need it all. We need it now.

That was Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin’s message on surging U.S. power demand. It sounds decisive. It’s ignorant. It treats electricity like a menu where you can order more generation and it just shows up.

Energy will be a serious constraint before the end of the decade. But the nearer-term obstacles are simpler and harder: permitting, build times, turbine and transformer backlogs, skilled labor, capital costs, and the hard limits of grid physics.

Ignore those constraints and you don’t get more electricity. You get cost overruns, schedule creep, and a widening gap between demand and deliverable capacity.

Growth and Uncertainty

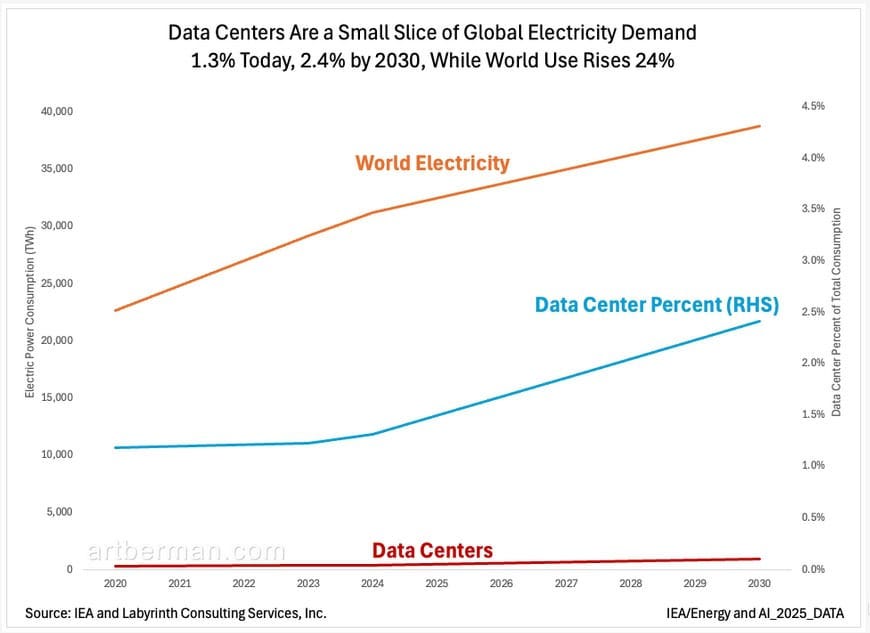

There’s almost as much hype about “soaring power demand” as there is about the AI supposedly driving it. Yes, data center electricity use could roughly double by 2030. But it’s doubling from a small base.

Data centers use about 1.3% of global electricity today, and the IEA sees that rising to only around 2.4% by 2030 (Figure 1). Over the same period, total world electricity demand is expected to rise on the order of 24%. So the idea that AI is the main driver of global power growth is badly overstated.

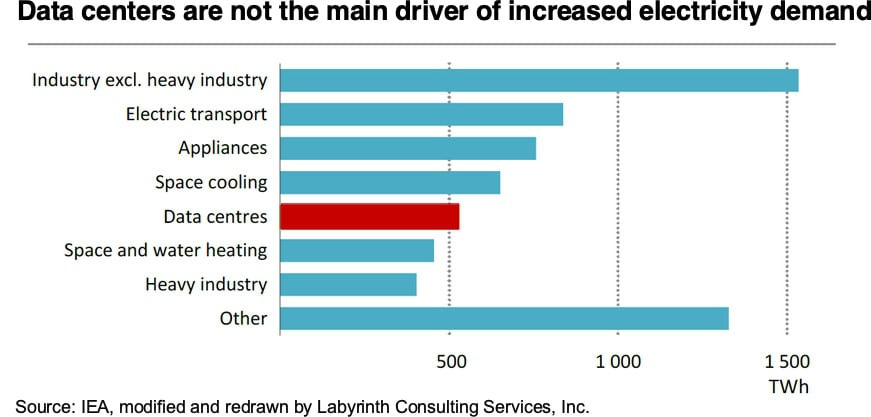

Most of the growth is boring, broad, and structural: industry and buildings (especially cooling), plus the steady electrification of transport and heating (Figure 2). Data centers matter operationally because their load is fast and geographically concentrated. But they’re still riding on top of a much bigger wave.

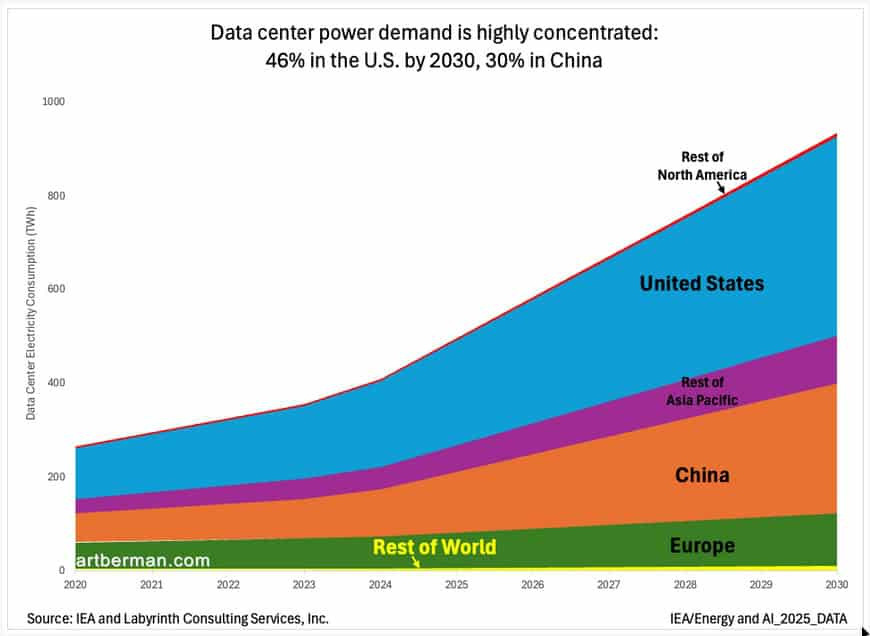

In the U.S. and other developed economies, data centers account for a larger share of incremental demand than they do globally. Even there, it’s still a fraction of total growth, not the whole story the headlines imply. What makes data centers uniquely disruptive is concentration: by 2030, nearly half of global data center electricity consumption is expected to be in the United States, and about 30% in China (Figure 3).

So yes, data centers are a major source of power stress in parts of the Global North. But the real constraints aren’t “do we have enough gas, coal, nuclear, and renewables?” The constraints are time, siting, equipment, skilled labor, capital, and grid deliverability.

System Risks

The first system risk is the shrinking dispatchable base. Nearly 79 GW of fossil-fired and nuclear retirementsare expected through 2034. Add another 43 GW of fossil units that have announced retirements but haven’t entered formal deactivation yet, and you’re over 115 GW of potential dispatchable thermal capacity coming off the board in the next decade.

Demand is rising. Dispatchable retirements are growing. And the replacement pipeline is heavy on solar, batteries, and hybrids that aren’t arriving fast enough or carrying the same reliability attributes as the thermal fleet they’re replacing (Figure 4).

That’s why capacity-only planning is increasingly misleading. In a system with weather-dependent and energy-constrained resources, you don’t just need nameplate megawatt capacity. You need on-demand generation, transmission to move it, and the essential reliability services thermal plants used to provide by default: voltage support, frequency response, ramping, and reserves.

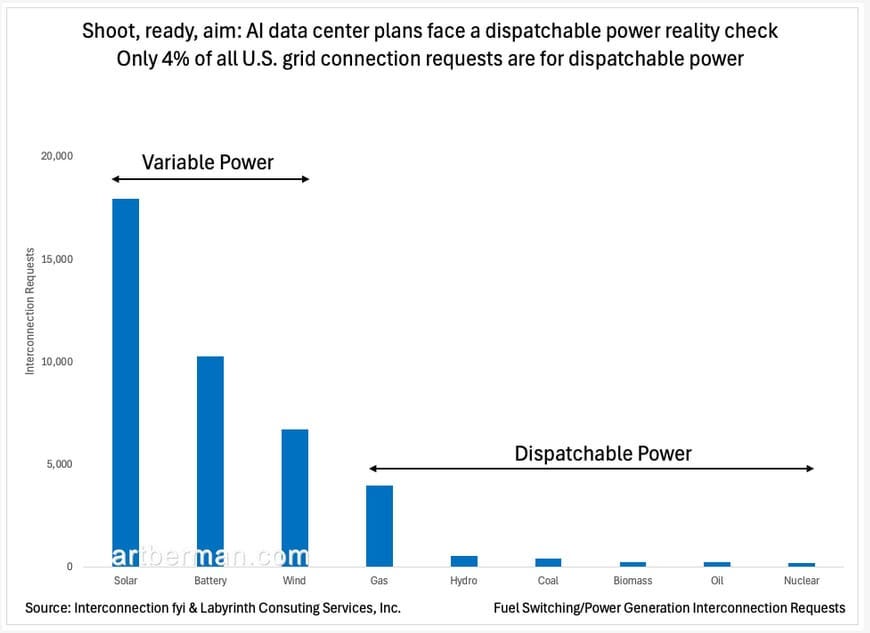

The second system risk is interconnection and delivery. Even if generation exists on paper, you may not be able to connect and move it. The interconnection queue is the grid’s choke point. Before a large generator plant can connect, the operator has to study whether the local and regional system can handle it. If not, you trigger upgrades: substations, transformers, lines, protection systems. Those take years to permit, procure, and build. Data centers can go up fast. Grid capacity can’t. The queue is where the mismatch becomes delay.

The third system risk is the supply chain.